Recognizing Concussions in Student-Athletes

Mlen Azurin/ Hawkview

Mlen Azurin/ Hawkview

In a recent study released this summer from Yale, there would be 49,600 fewer injuries among college male athletes per year and 601,900 among high school male athletes if contact sports were made noncontact. Ray Fair, an economics professor at Yale commented, “The issue really is that contact is the driving force in all these major injuries.”

An updated study by the Journal of the American Medical Association examined the brains of deceased former football players and found that “110 out of 111 donated brains of those who played in the NFL had CTE.”

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), according to the Concussion Legacy Foundation, is a “degenerative brain disease found in athletes, military veterans, and others with a history of repetitive brain trauma.” Long-term complications of CTE include memory loss, depression, Parkinson’s, dementia, as well as dizziness, headaches, hearing loss and tinnitus, speech difficulties, irritability, and aggression.

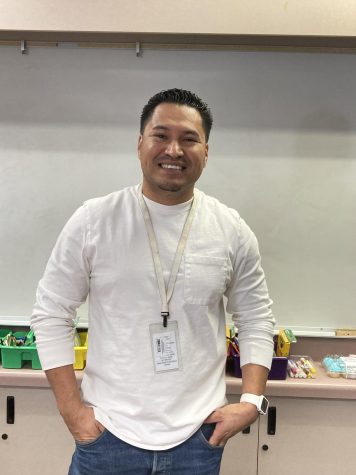

To prevent concussions in high school student-athletes, Coach Armstrong, head football coach and former athletic director, commented, “We don’t hit as much as we use to; we use a lot of what we call ‘hitting against shields and pads.’ We also limited our live contact to only one day a week.”

All high school coaches are required to take a free 30-minute online course through the National Federation of State High School Associations, an organization that governs all high school athletics across the country, regarding the safety of concussions. This course consists of player safety, signs of a concussion, and how to treat one. After completing the course, coaches receive a lifetime certification; however, the question remains, is that enough?

“If we see an athlete who has a possible concussion, we immediately pull them off of the court or field; the trainer on staff will take a look at them and if there is a physician on staff, they are the ones who will make the decision,” said Coach Ruiz, athletic director at LQHS. “If they feel that student-athlete could have a concussion, they will not be allowed to play.”

From 2005 to 2015, the number of diagnosed concussions doubled, according to a study from Northwestern University. Approximately 300,000 high school students endure concussions every year. In theory, helmets should protect American football players from injuries; however, the basic concept of helmets have not yet been innovative enough to protect the most valuable organ in the human body.

This year, Livermore High School in Livermore, Calif., committed to re-helmeting every football player with a state-of-the-art helmet that reduces the risk of a concussion. This $104,934 decision was made last fall after the author of “Concussion,” Jeanne Marie Laskas, made an appearance at local theater in Livermore. In an article by the East Bay Times, the Commissioner of Athletics for the North Coast Section of the California Interscholastic Federation, Gil Lemmon, was quoted saying that he believes they may be the first district to have made this move. The plan is that every year each helmet will be sent out for safety recertification, as the school board allocated replacement funds in the event a helmet does not pass the test.

Gordon Haskell (12) is on the varsity football team at LQHS. “I know that playing football comes with all types of risks, including concussions; but I continue to play because I love the sport, I wouldn’t give it up for anything.”

Juan Ruiz (12), who has been playing varsity football for three years, said, “I love taking the risk. Football is one of the few sports where you have full contact to hit someone; I continue to play because I like taking the risk. That’s the fun part about football – being able to hit.”

While high school football players are fiercely dedicated to their sport, it is the responsibility of schools and school districts to advocate for allocating enough funds, like Livermore Valley Joint Unified School District did, in order to protect student-athletes down the line.

Brysenia Miranda is a senior at La Quinta High School. She is in her first year of journalism. She enjoys playing basketball and hanging out with her family and friends in her free time. She is outgoing, adventurous, athletic, and very school spirited. She hopes that journalism will help her become a...

Steven Poole is a senior at La Quinta High School, where he plays for the soccer team, as well as for Desert United. This is his first year in journalism, where he hopes to meet new people and become a stronger writer. Poole plans to serve in the U.S. Army as an officer after graduating from a four-year...

Asa Castillon ♦ Dec 4, 2017 at 1:36 pm

man I never knew all the great risks when it comes to playing football. I’m glad to take the time to read this great story and learn how to play football a little more carefully.

jorge gutierrez ♦ Dec 4, 2017 at 1:35 pm

This hands down has got to be the best and most informative article I have ever read about concussions. I want more material from this author!!!